Junior Year, Split-Level-separated

During my junior year of high school, when my parents separated, I learned from my dad’s quiet wisdom and my mom’s practical love that survival means caring first.

MELORA'S ARCHIVE

~Melora

9/5/20252 min read

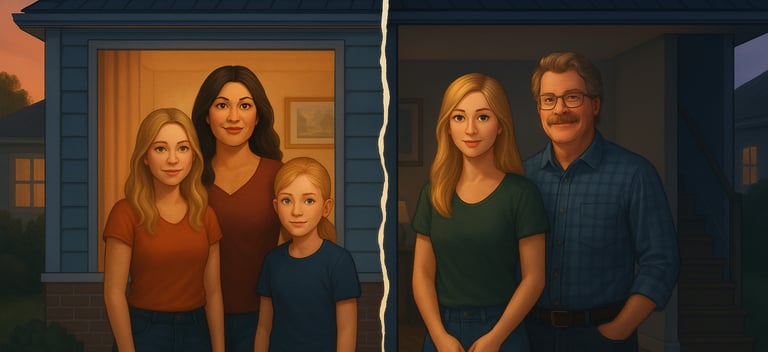

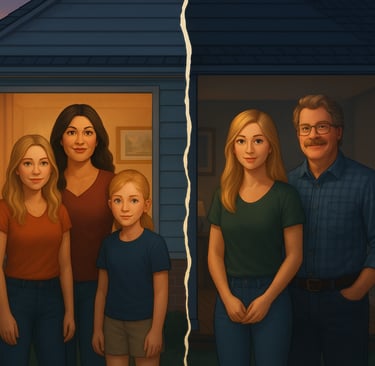

Halfway through my junior year, the seams finally gave. Mom and Dad separated, and suddenly the house sounded like it was learning to breathe on two lungs. The logistics were boring (they always are), but the feelings were not. It’s strange how a home can stay put while your belonging starts carpooling.

By then, I was deeply close with Dad. We had the same pace: quiet, then unexpectedly funny. He didn’t coach me through the separation. He just made space—campfire silence, riverbank calm, the kind that says, “We can sit here until the words catch up.”

Mom, on the other hand, loved us with motion. She worked hard to keep us cared for—new clothes, meals on the table, making sure school forms were signed, trying to hold the house together even when her marriage couldn’t be. Her way of surviving was making sure her daughters were okay first. She wasn’t unkind. She wasn’t distant. She was practical love embodied.

Separation makes you inventory your loyalties. I discovered mine were less about choosing sides and more about choosing skills. From Dad: make a fire from damp wood, even if it’s just metaphorical. From Mom: pack a bag that works, make sure everyone has what they need before you rest. From me: tell the truth, even when your voice is borrowed.

People talk about divorce like it’s a single moment, but it’s more like a season that arrives early and overstays. First comes the thaw—everyone’s a little soggy, a little relieved. Then the flowers—tiny, defiant, unexpected joy. Then the heat—resentments that bloom too fast. Eventually, if you’re lucky, you get a breeze: the part where you can open the windows again.

I still think about the split-level of that year: upstairs, downstairs; camp chair, slot machine; pageant polish, grass stain grit. We were never one thing, not even before the separation. Maybe that’s why we survived it. We already knew how to be mobile, to choose what fits in the trunk and what rides up front.

If I could tell my junior-year self anything, it would be this: You are not the glue. You are the storyteller. Glue dries out; stories travel. One day you’ll write it down and someone will nod in a kitchen three states away because it happened to them, too. And that nod will feel like a door opening in a house you haven’t lived in yet.

So here I am, telling it. Because the water’s moving, still. And I am not stuck—I’m just on my way.